From the folklore of Iceland

About the year 1000, when the Christian faith had hardly yet been heard of in Iceland, there dwelt at Bathstead, on the shores of Icefirth, in that far-distant land, a mighty chieftain, of royal descent and great wealth, named Thorbiorn. Though not among the first settlers of Iceland, he had appropriated much unclaimed land, and was one of the leading men of the country-side, but was generally disliked for his arrogance and injustice. Thorkel, the lawman and arbitrator of Icefirth, was weak and easily cowed, so Thorbiorn’s wrongdoing remained unchecked; many a maiden had he betrothed to himself, and afterwards rejected, and many a man had he ousted from his lands, yet no redress could be obtained, and no man was bold enough to attack so great a chieftain or resist his will. Thorbiorn’s house at Bathstead was one of the best in the district, and his lands stretched down to the shores of the firth, where he had made a haven with a jetty for ships. His boathouse stood a little back above a ridge of shingle, and beside a deep pool or lagoon. The household of Thorbiorn included Sigrid, a fair maiden, young and wealthy, who was his housekeeper; Vakr, an ill-conditioned and malicious fellow, Thorbiorn’s nephew; and a strong and trusted serving-man named Brand. Besides these there were house-carles in plenty, and labourers, all good fighting-men.

Not far from Bathstead, at Bluemire, dwelt an old Viking called Howard. He was of honourable descent, and had won fame in earlier Viking expeditions, but since he had returned lamed and nearly helpless from his last voyage he had aged greatly, and men called him Howard the Halt. His wife, Biargey, however, was an active and stirring woman, and they only son, Olaf, bade fair to become a redoubtable warrior. Though only fifteen, Olaf had reached full stature, was tall, fair, handsome, and stronger than most men. He wore his fair hair long, and always went bareheaded, for his great bodily strength defied even the bitter winter cold of Iceland, and he faced the winds clad in summer raiment only. With all his strength and beauty, Olaf was a loving and obedient son to Howard and Biargey, and the couple loved him as the apple of their eye.

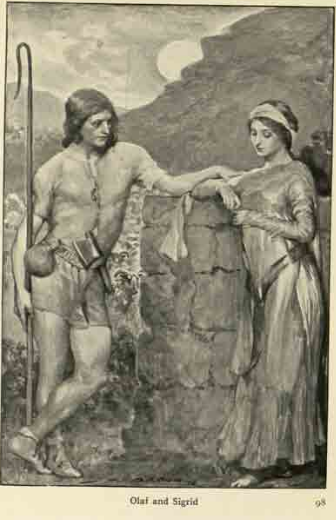

The men of Icefirth were wont to drive their sheep into the mountains during the summer, leave them there till autumn, and then, collecting the scattered flocks, tom restore to each man his own branded sheep. One autumn the flocks were wild and shy, and it was found that many sheep had stayed in the hills. When those that had been fathered were divided Thorbiorn had lost at least sixth wethers, and was greatly vexed. Some weeks later Olay Howardson went alone into the hills, and returned with all the lost sheep, having sought them with great toil and danger. Olaf drove the rest of the sheep home to their grateful owners, and then took Thorbiorn’s to Bathstead. Teaching the house at noonday, he knocked on the door, and as all men sat at their noontide meal, the housekeeper, the fair Sigrid, went forth herself and saw Olaf.

She greeted him courteously and asked his business, and he replied, “I have brought home Thorbiorn’s wethers which strayed this autumn,” and then the two talked together for a short time. Now Thorbiorn was curious to know what the business might be, and sent his nephew Vakr to see who was there; he went secretly and listened to the conversation between Sigrid and Olaf, but heart little, for Olaf was just saying, “Then I need not go in to Thorbiorn; thou, Sigrid, canst as well tell him where his sheep are now;” then he simply bade her farewell and turned away.

Vakr ran back into the hall, shouting and laughing, till Thorbiorn asked: “How now, nephew! Why makest thou such outcry? Who us there?”

“It was Olf Howardson, the great booby of Bluemire, bringing back the sheep thou didst lose in the autumn.”

“That was a neighbourly deed,” said Thorbiorn.

“Ah! But there was another reason for his coming, I think,” said Vakr. “He and Sigrid had a long talk together, and I saw her put her arms round his neck; she seemed well pleased to greet him.”

“Olaf may be a brave man, but it is rash of him to anger me thus, by trying to steal away my housekeeper,” said Thorbiorn, scowling heavily. Olaf had no thanks for his kindness, and was ill received wherever he came; yet he came often to see Sigrid, for he loved her, and tried to persuade her to wed him. Thorbiorn hated him the more for his open wooing, which he could not forbid.

The next year, when harvest was over, and the sheep were brought home, again most of the missing sheep belonged to Thorbiorn, and again Olaf went to the mountains alone and brought back the stray ones. All thanked him, except the master of Bathstead, to whom Olaf drove back sixty wethers. Thorbiorn had grown daily more enraged at Olaf’s popularity, his strength and beauty, and his evident love for Sigrid, and now chose this opportunity of insulting the bold youth who rivalled him in fame and in public esteem.

Olaf reached Bathstead at noon, and seeing that all men were in the hall, he entered, and made his way to the dais where Thorbiorn sat; there he leaned on his axe, and gazed steadily at the master, who gave him no single word of greeting. Then every one kept silence, watching them both.

At last Olay broke the stillness by asking: “Why are you all dumb? There is no honour to those who say naught. I have stood here long enough and had no word of courteous greeting. Master Thorbiorn, I have brought home thy missing sheep.”

Vakr answered spitefully: “Yes, we all know that thou hast become the Icefirth sheep-drover; and we all know that thou hast come to claim some share of the sheep, as any other beggar might. Kinsman Thorbiorn, thou hadst better give him some little alms to satisfy him!”

Olaf flushed angrily as he answered: “Nay, it is not for that I came; but, Thorbiorn, I will not seek thy lost sheep a third time.” And as he turned and strode indignantly from the hall Vakr mocked and jeered at him. Yet Olaf passed forth in silence.

The third year Olaf found and brought home all men’s sheep but Thorbiorn’s; and then Vakr spread the rumour that Olaf had stolen them, since he could not otherwise obtain a share of them. This rumous came at last to Howard’s ears, and he unbraided Olaf, saying, when his son praised their mutton, “Yes, it is good, and it is really ours, not Thorbiorn’s. It is terrible that we have to bear such injustice.”

Olaf said nothing, but, seizing the leg of mutton, flung it across the room; and Howard smiled at the wrath which his son could no longer suppress; perhaps, too, Howard longed to see Olaf in conflict with Thorbiorn.

While Howard was still upbraiding Olaf a widow entered, who had come to ask for help in a difficult matter. Her dead husband (a reputed wizard) returned to his house night after night as a dreadful ghost, and no man would live in the house. Would Howard come and break the spell and drive away the dreadful nightly visistant?

“Alas1” replied Howard, “I am no longer young and strong. Why do you not ask Thorbiorn? He accounts himself to be chief here, and a chieftain should protect those in his country-side.”

“Nay,” said the widow. “I am only too glad if Thorbiorn lets me alone. I will not meddle with him.”

Then said Olaf: “Father, I will go and try my strength with this ghost, for I am young and stronger than most, and I deem such a matter good sport.”

Accordingly Olaf went back with the widow, and slept in the hall that night, with a skin rug over him. At nightfall the dead wizard came in, ghastly, evil-looking, and terrible, and tore the skin from over Olaf; but the youth sprang up and wrestled with the evil creature, who seemed to have more than mortal strength. They fought grimly till the lights died out, and the struggle raged in the darkness up and down the hall, and finally out of doors. In the yard round the house the dead wizard fell, and Olaf knelt upon him and broke his back, and thought him safe from doing any mischief again. When Olaf returned to the hall men had rekindled the lights, and all made much of him, and tended his bruises and wounds, and counted him a hero indeed. His fame spread through the whole district, and he was greatly beloved by all men; but Thorbiorn hated him more than ever.

Soon another quarrel arose, when a stranded whale, which came ashore on Howard’s land, was adjudged to Thorbiorn. The lawman, Thorkel, was summoned to decide to whom the whale belonged, and came to view it. “It is manifestly theirs,” said he falteringly, for he dreaded Thorbiorn’s wrath. “Whose saidst thou?” cried Thorbiorn, coming to him menacingly, with drawn sword. “Thine,” said Thorkel, with downcast eyes; and Thorbiorn triumphantly claimed and took the whale, though the injustice of the decree was evident. Yet Olaf felt no ill-will to Thorbiorn, for Sigrid’s sake, but contrived to render him another service.

Brand the Strong, Thorbiorn’s shepherd, could not drive his sheep one day. Olaf met him trying to get his frightened wethers home; it seemed an impossible task, because an uncanny human form, with waving arms, stood in a narrow bend of the path and drove them back and scattered them. Brand told Olaf all the tale, and when the two went to look, Olaf saw that the enemy was the ghost of the dead wizard whom he had fought before. “Which wilt thou do,” said Olaf, “fight the wizard or gather thy sheep?”

“I have no wish to fight the ghost; I will find my scattered sheep,” said Brand; “that is the easier task.

Then Olaf ran as the ghost, who awaited him at the top of a high bank, and he and the wizard wrestled again with each other till they fell from the bank into a snowdrift, and so down to the seashore. There Olaf, whose strength had been tried to the utmost, had the upper hand, and again broke the back of the dead wizard; but seeing that had been of no avail before, he took the body, swam out to sea with it, and sank it deep in the firth. Ever after men believed that this part of the coast was dangerous to ships.

Brand thanked the youth much for his help, and when he reached bathstead related what Olaf had done for him. Thorbiorn said nothing, but Vakr sneered, and called Brand a coward for asking help of Olaf. The strife grew keen between them, almost to blows, and was only settled by Thorbiorn, who forbade Brand to praise Olaf or to accept help from him. His ill-will grew so evident to all men that Howard the Halt decided, in spit of Olaf’s reluctance, to remove to a homestead on the other side of the firth, away from Thorbiorn’s neighbourhood.

That summer Thorbiorn decided to marry. He wooed a maiden who was sister of the wise Guest, who dwelt at the Mead, and Guest agreed to the match on condition that Thorbiorn should renounce his injustice and evil ways; to this Thorbiorn assented, and the wedding was held shortly after. Thorbiorn had said nothing to his household of his proposed marriage, and Sigrid first heard of it when the wedding was over, and the bridal party would soon be riding home to Bathstead. Sigrid was very wroth that she must give up her control of the household to another, and refused to stay to serve under Thorbiorn’s wife; accordingly she withdrew from Bathstead to a kinsman’s house, taking all her goods with her. Thorbiorn raged furiously on his return, when he found that she was gone, for her wealth made a great difference to his comfort, and threatened dire punishment to all who had helped her. Olaf continued his wooing of Sigrid, and went to see her often in her kinsman’s abode, and they loved each other greatly.

One day when Olaf had been seeking some lost sheep he made his way to Sigrid’s house, to talk with her as usual. As they stood near the house together and talked Sigrid looked suddenly anxious and said: “I see Thorbiorn and Vakr coming in a boat over the firth with weapons beside them, and I see the gleam of Thorbiorn’s great sword Warflame. I fear they have done, or will do, some evil deed, and therefore I pray thee, Olaf, not to stay and meet them. He has hated thee for a long time, and the help thou didst give me to leave Bathstead did not men matters. Go thy way now, and do not fall in with them.”

“I am not afraid,” said Olaf. “I have done Thorbiorn no wrong, and I will not flee before him. He is only one man, as I am.”

“Alas!” Sigrid replied, “how canst thou, a stripling of eighteen, hope to stand before a grown man, a mighty champion, armed with a magic sword? Thy words and thoughts are brave, as thou thyself art, but the odds are too great for thee; they are two to one, since Makr, ever spiteful and malicious, will not stand idle while thou art in combat with Thorbiorn.”

“Well,” said Olaf, “I will not avoid them, but I will not seek a contest. If it must be so, I will fight bravely; thou shalt hear of my deeds.”

“No, that will ever be; I will not live after thee to ask of them,” said Sigrid.

“Farewell now; live long and happily!” said Olaf; and so they bade each other farewell, and Olaf left her there, and went down to the shore where his sheep lay. Thorbiorn and Vakr had just landed, and they greeted each other, and Olaf asked them their errand. “We go to my mother,” said Vakr.

“Let us go together,” replied Olaf, “for my way is the same in part. But I am sorry that I must needs drive my sheep home, for Icefirth sheep-drovers will; become proud if a great man like thee should join the trade, Thorbiorn.”

“Nay, I do not mind that,” said Thorbiorn; so they all went on together; and as he went Olaf caught up a crooked cudgel with which to herd his sheep; he noticed, too, that Thorbiorn and Vakr kept trying to lag behind him, and he took care that they all walked abreast,

When the three came near the house of Thordis, Vakr’s mother, where the ways divided, Thorbiorn said: “Now, nephew Vakr, we need no longer delay what we would do.” And then Olaf knew that he had fallen into their snare. He ran up a band beside the road, and the two set on him from below, and he defended himself at first manfully with the crooked cudgel; but Thorbiorn’s sword Warflame sliced this like a stalk of flax, and Olaf had to betake himself to axe, and the fight went on for long.

The noise of the fray reached the ears of Thordis, Vakr’s mother, in her house, so that she sent a boy to learn the cause, and when he told her that Olaf Howardson was fighting against Thorbiorn and Vakr she bade her second son go to the help of his kinsfolk.

“I will not go,” said he. “I would rather fight for Olay than for them. It is a shame for two to set on one man, and they such great champions too. I will not be the third; I will not go.”

“Now I know thou art a coward,” sneered his mother. “Daughter, not son, thou art, too timid to help thy kinsfolk. I will show thee that I am a braver daughter than thou a son!”

By these words Thordis so enraged her son that he seized his axe and rushed from the house down the hill towards Olaf, who could not see the new-comer, because he stood with his back to the house. Coming close to Olaf, the new assailant drove the axe in deep between his shoulders, and when Olaf felt the blow he turned, and with a mighty stroke slew his last enemy. Thereupon Thorbiorn thrust Olaf through with the sword Warflame, and he died. Then Thorbiorn took Olaf’s teeth, which he smote from his jaw, wrapped them in cloth, and carried them home.

The news of the slaughter was at once told by Thorbiorn (for so long as homicide was not concealed it was not considered murder), and told fairly, so that all men praised Olaf for his brave defence, and lamented his death. But when men sought for the fair Sigrid she could not be found, and was seen no more from that day. She had loved Olaf greatly, had seen him fall, and could not live when he was dead; but no man knew where she died or was buried.

The terrible news of Olaf’s death came to Howard, and he sighed heavily and took to his bed for grief, and remained bedridden for twelve months, leaving his wife Biargey to manage the daily fishing and the farm. Men though that Olaf would be for ever unavenged, because Howard was too feeble, and his adversary too mighty and too unjust.

When a year had passed away Biargey came to Howard where he lay in his bed, and bade him arise and go to Bathstead. Said she: “I would have thee claim wergild for our son, since a man that can no longer fight may well prove his valour by word of mouth, and if Thorbiorn should show any sign of justice thou shalt not claim too much.”

Howard replied: “I know it is a bootless errand to ask justice from Thorbiorn, but I will do thy will in this matter.”

So Howard went heavily, walking as an old man, to Bathstead, and, after the usual greetings, said: “I have come to thee, Thorbiorn, on a great matter – to claim wergild for my dead son Olaf, whom thou didst slay guiltless.”

Thorbiorn answered: “I have never yet paid a wegild, though I have slain many men – some say innocent men. But I am sorry for thee, since thou hast lost a brave son, and I will at least give thee something. There is an old horse named Dodderer out in the pastures, grey with age, sore-backed, too old to work; but thou canst take him home, and perhaps he will be some good, when thou hast fed him up.”

Now Howard was angered beyond speech. He reddened and turned straight to the door; and as he went down the hall Vakr shouted and jeered; but Howard said no word, good or bad. He returned home, and took to his bed for another year.

Sources:

Chapter 6, Hero-myths and Legends of the British Race, M.I. Ebbutt, 1910