Introduction

We are now deep into the internet age of art, where distribution for art is widely available, making entry easy. However, getting noticed is difficult in such a saturated market. Similar difficulties are faced by corporate media which is increasingly running out of ideas, thus turning to recycling old franchises. What, therefore, are the future prospects for art as independents, the middle market, and corporations adapt to this new world?

Independent Art

Independent art will continue to be defined as it was in the past. The positive aspect of it is that the art is potentially more original and interesting, especially when compared to mainstream alternatives which are typically tightly controlled, and hence follow publisher trends . The negative is that it doesn’t have the budget of larger productions, meaning it will have less production quality. This is less noticeable in genres like music or writing (where independent tendencies are typically advantages rather than downsides), however it will continue to affect more difficult productions like games and movies for the foreseeable future. There is also the issue that independent art is riskier from an audience perspective, which makes . The middle market is also positioned to take advantage of both independent media trends and mainstream technology, able to put more money into projects than indies, while also being more agile than large companies.

The key factor of why art became commercialized is the difficulty in distribution. Even now, in the age of extremely accessible printing, the average person doesn’t have the money to order a print job of books and mail them out in quantities that would make it worth their while. This is where the solution of digital media offers itself. The average person can easily put up a Pdf file on a website and sell that. However, the biggest issue with this method of selling goods is discovery. Unfortunately the largest search engines in the world (mostly Google) are currently designed to direct people to large information sites and corporate sponsored sites (often for goods only vaguely related to search terms). This makes discovering smaller sites markedly difficult with mainstream search engines. Alternative engines like Duck Duck Go and Bing are better in this regard, but also have a much smaller market share. This is why small sites typically have to rely on networking or external media to get traffic.

This then leads to people relying on larger established sites such as Amazon (for books), Apple/Google store (for music), Apple/Google/Steam/Xbox/Playstation (for games), etc. This is where most sales are expected to take place, and is where larger search engines will generally send people. Of course, most other people have the same idea, meaning that success on such platforms is hardly guaranteed amongst all the other competition. There will always be breakout hits, but most works will unfortunately go unnoticed. Furthermore, one also has to contend with established authors and publishing companies that already have earned their fans (in other words, patience is required for any work). While this is a more open sort of publishing than used to exist, it has ultimately just shifted the way in which an author relies upon a distribution company. They are no longer subjected to an editor or corporate mandates, but that also means that promotion is in the hands of an author, not the distribution company. And in the end, one’s account ultimately exists at the whim of a company and how long it wishes to make its services available to you.

With uncertain success, most new authors typically write in their free time while holding a primary job. Some elements of this dynamic change once one has an audience and body of work (and I’m going by what I’ve heard from other authors here, as I’m new to this field myself). Having an audience opens the potential of using things like crowd funding and patronage to support ones work. It is technically possible to acquire crowd funding without a built in audience, but it requires both slick marketing skills and some measure of luck.

Other sorts of independent media have their own challenges. Game developers likely have an easier time getting noticed compared to books, usually favoring digital marketplaces like Steam or the Epic Games storefront, however that comes at the cost of long development cycles. One of the biggest advantages to independent game development is that there is a large built in audience of gamers who dislike the state of modern AAA gaming, and thus confine their purchases to AA and independent games.

Music is almost entirely a matter of digital patronage now, since the vast majority of artist’s discographies will end up online whether they like it or not. This provides some measure of profit and the potential for exposure, however it also means that the vast majority of the audience will choose to listen on streaming services rather than outright purchase the songs. Distribution is easy with sites like Bandcamp, and storefronts like Apple being well known for music distribution. It’s entirely possible to play at smaller venues, though this requires some effort to seek out contacts in the immediate area.

Independant television is in an interesting place. On the one hand, it is entirely possible to put up videos on Youtube and get numerous views. It is more difficult to make consistent money at this, especially in the amount which warrants the time it takes to develop some types of media. There are a number of channels which act as collectives of independent short films, with many specializing in fields such as horror or 3D animation. The closest thing to an easy external distribution network for indie movies and TV series is Amazon. However, this runs into the issue of requiring a great deal of views to make it worthwhile. Independent distribution is a possibility, but runs into the same shipping issues of other products (though producing DVDs is substantially cheaper than books). This typically leads most of the higher budget small productions to seek streaming deals with Netflix, Hulu, etc. While these services always crave more content to offer people, and quality is not their primary concern, there is no guarantee that one can get on those services.

If I had to speculate, I think that the future of independent art will probably be found in networked online collectives, consisting of perhaps several dozen content creators. Such a network could found a centralized site which could serve as a digital distribution network, and each content creator would fund the site and direct their followers from social media to it. This will then achieve mutual exposure, from which all could profit. Physical printing and distribution would probably have to be handled externally for printed media, though it is not impossible to do it alone. Examining the current state of privately distributed printed goods, the primary issue is shipping costs, which are especially prohibitive to international customers, and often add 40% extra cost to something like a book. While this is not terrible for certain high priced goods or multiple orders, it is prohibitive for ordering a single book, something that is an issue for people who prefer physical goods and are interested in keeping up with an author.

The Future of Corporate Art

Corporate art has been adapting in its own way to the changing times. With much more money to throw at problems, there are many ways it could go (and undoubtedly many places in which plans will fail). One of the most common trends now is for corporations to act as the publishers of media instead of directly creating it. Thus one finds examples of corporations funding small studios to produce TV shows, movies, or games on a contractual basis, which are then distributed by the corporation to a network of stores and streaming services. Of course, this does come at the cost of independence, the same cost which was demanded in the original era of pop culture. The move from direct production control to distribution control, achieved through publishing rights or exclusive licensing, is likely the greatest future trend for corporate art.

With streaming taking focus, one can predict that publishing large amounts of content for relatively inexpensive costs will take focus. Animation and contemporary drama are natural fits for lower priced shows, likely substituted with occasional marquis elements. It will be interesting to see what happens to streaming once the supply of 2020s era movies (i.e. the ones denied good theatrical releases, forcing them to streaming services) dries up.Other than that, I predict that big companies will likely target fewer releases, mostly made up of nostalgia bait, to cinemas. It’s also worth noting that the two biggest cinematic releases in 2022 have both been Chinese films (which just goes to show that other areas of the world no longer rely upon western entertainment).

Book publishers will continue to decline, especially as the market goes further towards independent or crowdfunding. There are already signs that some publishing companies, like DC comics, are being put into maintenance mode by their corporate owners. This will likely mean that companies will publish either well known authors or internet personalities which are presumed to come with an audience.

For the purposes of the rest of this article, I want to focus on some of the negative trends we see in corporate art, those which are Anti-Art in nature. This primarily focuses on western art, and undoubtedly the market in East Asia and developing markets like India, the Middle East, Africa, and South America are different.

The Death of Style: Alegria

Starting off with a topic that will surprise no artist, let’s get into the obvious poster for corporate art decline. If you’ve used a corporate product recently, especially if you’ve been on a corporate website, you’ve seen a particularly hideous Anti-Art style known as Alegria. Here are some examples:

Here’s a good before and after image to drive the point home (and this is from an anti-virus software company):

You might say that this is all talentless garbage, and you would be correct. This art is often illustrated by actual artists, however it does not allow them to show their actual talent. So then, how did this style come to be? It is the result of an “artstyle” specifically designed to be cheap, quick to manufacture, and purposefully inoffensive by corporate mandate. Facebook commissioned the style, and then exported it to the rest of silicon valley. Then, monkey-see-monkey-do, most western tech companies adopted it because they wish to ape the big players in the market. Most artists working on the stuff hate it, but they’re also aware that it’s designed to the easy enough to produce that they can be replaced at any time. Because of this factor, artistic skill is barely involved in its creation, therefore it is easy to hire new and inexperienced artists who work for cheap. Characters are frequently portrayed engaging in corporate sanctioned displays of fun, yet the art style acts against any sort of inspiration of pleasure one could take in it. Indeed, I would argue that once one gets past all the bright colors and pseudo-fun, there is a chillingly dehumanizing and demoralizing idea at the core of this art, one which perfectly summarizes what Anti-Art means. It inspires nobody, it is identified with by nobody, purposefully means nothing, and is despised by the true artists ordered to create it. Thus it reveals the dehumanizing and cheap characteristics of modern corporations.

I would also include the recent trend in 3D towards the “blob person” aesthetic. It is similarly destructive and anti-artistic:

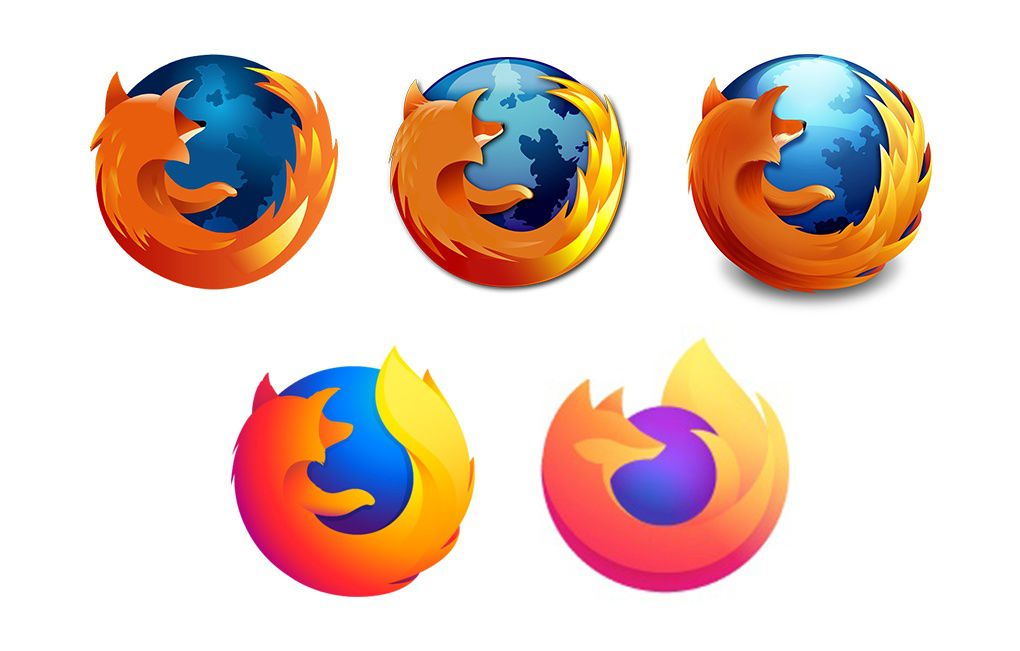

The Death of Identity: Design Simplification

Do you remember the classic product logos from years ago? Each one was designed to be recognizable and immediately call to mind products offered by a company. Now a trend of extreme minimalism has emerged which displays a preference for simplified logos.

Minimalism itself is not something to condemn. Depending on the purpose, it can absolutely be the correct artistic choice to make. However, in the case of this industry wide trend, it is not hard to see that this lack of personality has resulted in brands feeling devoid of character and homogenized. Some posit that simplified logos are used because minimalist designs present better on cell-phones. Perhaps, but there are also numerous cases of switching logos to pure text, removing any stylization. If a logo is meant to represent what a company is, what does it say when all personality is removed? Well, it says that all that logo represents is yet another sterile blob company amongst all the rest. I believe an aspect of this is an intentional trend towards mass corporate conformity, as the following might well demonstrate.

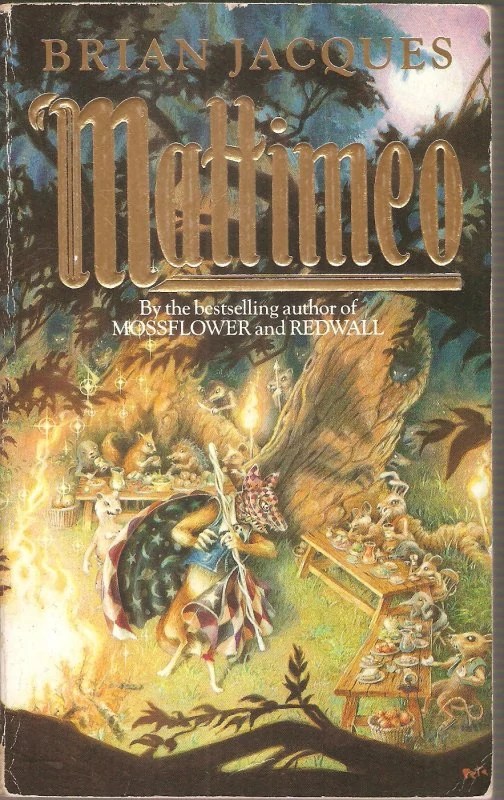

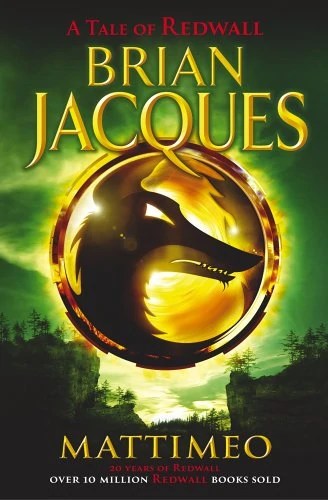

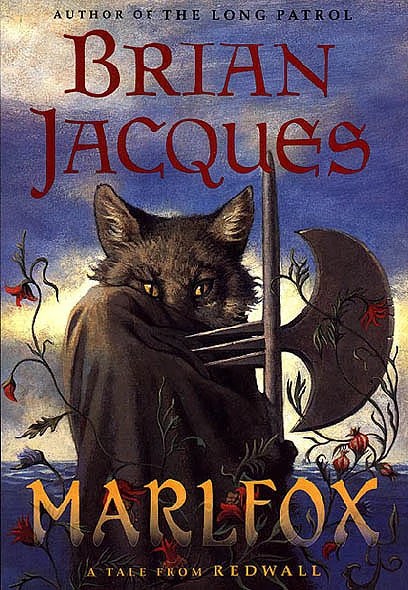

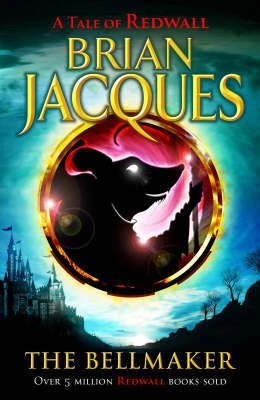

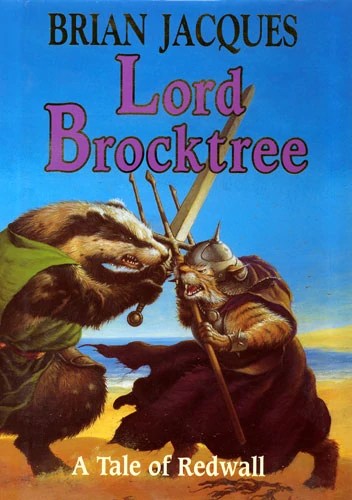

This personality destroying simplification is not limited to just logos. Book covers are also notorious victims of this trend. To give an example, one of my favorite book series as a child was Redwall, which I followed up to the age of 14. The series was about the adventures of anthropomorphic animals in a medieval fantasy setting. The covers were either stylized to be semi-realistic paintings (in the case of the hard cover books), or more cartoon-like, though proportionally realistic, illustrations (in the case of the soft cover books). They usually showcased the main characters of the book in character defining scenes, giving you a good idea of what was inside (as good covers should). Anyways, the modern books got re-released, and now the cover art is made up of random background scenery and a minimalist badge which tells you nothing about the story inside. Each book looks more similar to one another than the previous entries, however any sense of adventure and wonder has been sacrificed for generic series identity. Without knowing the nature of the series, one would not be inclined to purchase it on the basis of these covers.

Old Redwall Covers

New Redwall Covers

Here are some more comparisons

One last time, style and creativity sacrificed for conformity.

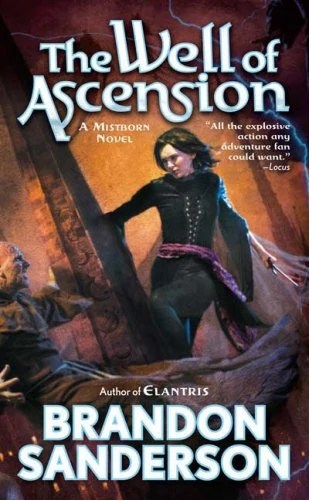

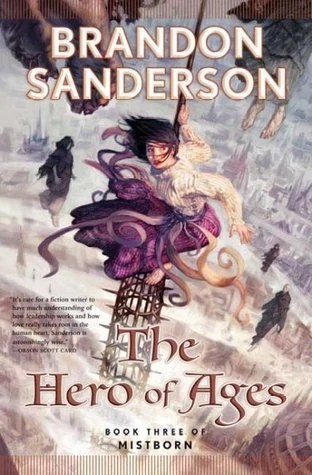

Similarly, I acquired the original Mistborn trilogy last year. The books are good and fun, but you wouldn’t know that from the reissued covers which tell you absolutely nothing about them, instead displaying vague scenes that have no defining value to them. Just like with Redwall, if you have not heard anything about Mistborn, you’d probably walk by it on a bookshelf without giving it a second look. The original book covers had illustrations of the primary character, usually performing a daring acrobatic feat, which gives a good idea of the magic system employed in the book:

Without knowing the inner reasoning of mainstream publishers, we can only speculate as to why this choice is made. Some think it’s done to appeal to ensure strict conformity to an identifying brand characteristic (i.e. ensure that all covers are of a similar color with consistently placed lettering, for example). Others think that they’re designed purely to conform to the current corporate aesthetic. Still others think that it’s done to drive traffic away from older books to newer releases, which seem to still get properly illustrated covers (and often priced more expensively). You can choose what you wish to believe about this matter.

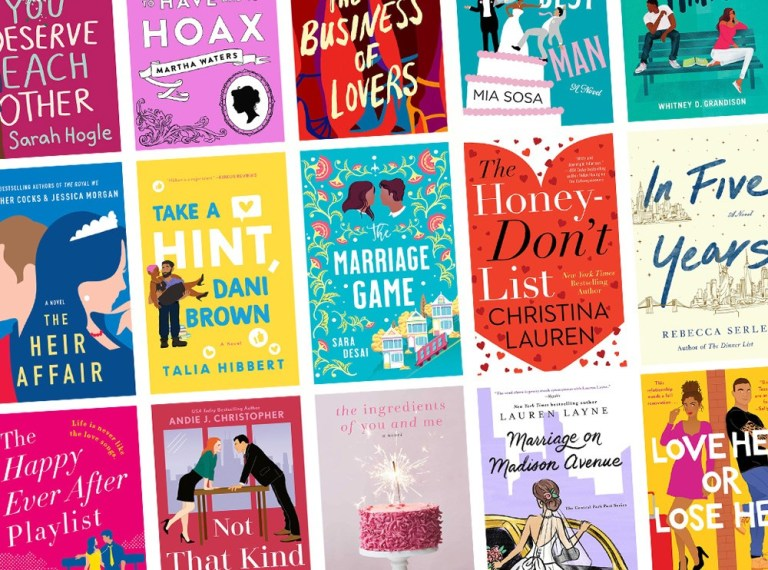

Just to put the point home, here are several collages of similarly bland themed books:

The Death of Seriousness: Video Game Art

This subject might be hard to explain for non-gamers, since I know that video games already have a reputation (somewhat well earned) for having exaggerated styles. However, when video games were historically wacky, it was done in games in which it was appropriate, such as cartoony games or games which parodied the action genre. Serious games have a certain art style about them, as do games which are at least somewhat set in reality.

In recent years there has been a big push amongst gaming companies to promote an ugly artstyle that can best be described as a mixture between millennial poser-punk culture, cutsie outfits, lol-random memes, and neon lights. Imagine, for example, that you went into battle dressed up as a rainbow unicorn with a half shaved head, hair dyed green, and a vest with blinking tail lights attached to it. Now imagine that the player next to you is dressed up in a pink teddy bear outfit holding an assault rifle decorated with Christmas lights. And then both characters start making MCU-like snarky quips as they’re gunning enemies down, performing silly dances in between action. And trust me, as someone who has seen several games I enjoyed go down this route, it is always a first sign of the end. Here are some examples:

This is basically ADHD the art style, and seems like a corporate attempt to appeal to the youth, designed by absolute lunatics. In standard games, one can understand the fantasy, perhaps misguided at times, of wanting to be a knight, a cool special forces operative, a pirate, or something similar. What then is the fantasy that’s being fuelled and catered to by having players run around looking like they’ve escaped from a mental asylum? There is no seriousness, nor any respect for what one is trying to represent. There is only catering to the absolute lower part of the playerbase, and that is to the shame of any company participating in this art catering to self-destructive fantasies.

Artificially Trending Media

The newest form of advertising utilizes so-called guerrilla marketing tactics. Guerrilla marketing in an attempt to move away from obvious marketing, made up of sponsored ads and the like, instead attempting to advertise to people inconspicuously. Depending on how blatant the company wishes to be, this can include paying influencers to use and display their products, or even the use of bot networks to generate positive attention and fake a consensus.

Companies can easily sponsor ads of social media sites like Twitter, Facebook, Tictoc, and Youtube, which appear deceptively amongst other legitimate videos, tweets, and statuses. This is done in an attempt to artificially make products achieve a “viral” or “trending” status. In many cases these advertisements are accompanied by thousands of likes, bland supportive comments, etc. In the case of accompanying bot networks, the intention is to create an initial impulse that will be picked up by real people. Compared individually, the bot posts become obviously fake, but most people won’t view comment chains long enough to establish this, instead allowing themselves to be wowed by numbers.

Another frequent tactic on social media is to buy followers in order to give the illusion of a larger audience than one actually has. Followers purchased in this way are provided by so-called “bot-farms,” which are typically large numbers of internet-capable cell-phones that are capable of rapidly deploying messages on various social media platforms. Countries like China have these in wide-spread use, and they are used to both market products and artificially manipulate online conversations (by giving the illusion of one perspective having overwhelming support, or by setting up blatant strawmen for another perspective). With a bit of tweaking, these can be easily harnessed for use by western companies (and yes, this is technically against the terms of service for most social media companies, but it happens regardless). For example, consider the phrase: “Wow, I thought this episode of (insert show name) was awesome!” A bot network could take this phrase and change up a world or two between different posts, deploy a hundred tweets, statuses, or comments, and thus give the illusion that many people enjoyed the show. This in turn forges a consensus bubble where people are more likely to express enjoyment of a product in order to be seen as a member of the popular “in-group.”

A famous example of artificially trending media, apparently occurring due to an algorithm glitch, occurred recently when a decades old Japanese song called Plastic Love was suddenly put as a trending video by the Youtube algorithm, racking up tens of millions of views overnight. What this demonstrates is that algorithms can artificially push content onto viewers, thus creating manipulated inorganic trends. And this is how new corporate channels, musicians, movie trailers, music videos, etc. are put into the spotlight on such platforms. One need only remember that the front page of Youtube, the trending feed of Twitter, etc. are all curated rather than organically developed.

Gaming the review systems is nothing new. It’s been a long term secret that the New York Times bestseller list was historically compiled from books sales made by select retailers in New York City. One could effectively game that system by simply buying several hundred books from a retailer. Nowadays, of course, the bestseller list is simply artificially curated from a list of possible best sellers.

This all raises the question of how real public opinion is on the internet. Especially on sites which have easier to game content, it seems like it would be a good idea to take what you read with a measure of scepticism. Are we truly seeing massive blockbusters and popular franchises, or are we experiencing some measure of manipulation?

There’s an interesting, if depressing, concept known as the “Dead Internet Theory,” which posits that much of the modern internet is actually made up of bots communicating together for the purposes of artificial manipulation. Its basic thesis may be exaggerated, however one can imagine that if even ten or twenty percent of accounts are indeed bots, then they could easily be used to create artificial trends and consensus.

NFTs

What is an NFT you ask? Well, an NFT (or Non-fungible token) is essentially a piece of code that links to a piece of data on a server. Essentially, an NFT holds a queue place on a server, which is accounted for in its operation, and people buy, sell, and hold these places. Explained like that it sounds simple enough, and also like something nobody who isn’t a massive computer nerd would be interested in. You would be correct on that point. Whatever potential something like a blockchain has, it is something of interest to computer scientists, not the general population. Yet, if that is the case, then why have NFTs become popularized?

Simply put, in a genius advertising move, someone came up with the idea to tie uniquely generated artwork to NFTs. Thus, instead of purchasing a place in a queue, one is purchasing a place in a queue marked by a poster. However, not all is as it seems. Most buyers are under the false impression that they “own” the copyright to the piece of digital artwork attached to an NFT that they’ve purchased. Because of this, and some recent advertising pushes by online celebrities (such as Jake Paul), some NFTs have been sold for anywhere from ten thousand dollars to several million (though it should be noted that, as with crypto-currencies, NFTs are well known vectors of money laundering, so some of these probably don’t represent real purchases). Regardless, the sales of these NFTs are actually occurring under a false pretense. No ownership of image copyright is transferred by the purchase of an NFT. Some producers of NFTs say that it is (specifically the monkey NFT and a few others), but there isn’t really any legal mechanism that recognizes an NFT as a valid way to control the copyright of such art. This is not to mention the numerous cases of outright stolen images that are used in NFTs.

(I’ll also note the ridiculousness of purchasing a piece of digital art for that sort of money when one can literally have cartoony art of a much better quality commissioned for <50$).

This is another example of Anti-Art to my mind. There is no story or idea behind NFTs, and rather than the art being representative of what is being purchased (as with a product mascot), it is rather there to disguise what is being purchased.

NFTs are not limited to crypto speculators. There have already been forays of corporate interest into NFTs, most notably with the Video Game company Ubisoft, the WWE wrestling company, various car companies, etc. Several game companies have expressed interest in using NFTs to sell unique cosmetic icons and avatars for their games, which is just another method of increasing the burdensome amount of microtransactions in gaming.

If there’s one upside to all this, we know that the Ubisoft foray into NFTs proved to be an absolute failure, one which earned them a great deal of negative advertising. Combined with the hostility of China and Russia towards crypto-currencies, many speculate that the NFT market is currently on its way out.

Streaming and Advertising

Streaming, in its current state, isn’t profitable. A bold claim I know, but it is true. Each streaming company has spent an immense amount of money to set up their sites, such that even at large numbers of registrations don’t cover them. Furthermore, the largest companies such as Warner Bros, Disney, and Netflix was each in debt to the tune of billions or tens of billions of dollars. If this isn’t bad enough, streaming is not a one stop show since they must account for the continuous cost of employees, servers across the world, and regularly provided content (content that is very expensive to produce, as even animated shows now often cost in excess of a million dollars an episode).

One needn’t even mention the strain that streaming everything (contrasted with one time downloads) puts on the internet as a whole. Modern Youtube alone consumes more bandwidth than the entire internet prior to its release. All of this is ultimately chasing the dream of having a consistently paying audience, who rent products on a continual basis, instead of an audience that pays once for physical media or an experience.

The obvious conclusion is that advertising will eventually be introduced to recuperate losses. What will the nature of this future advertising be? Will it be the old fashioned video before/during a show, or something else?

One suggestion is that technology is increasingly being developed to integrate them into the films themselves. Historically this was done by product placement, where a character on screen was shown conspicuously consuming a product, with the hope of subliminally influencing the audience to purchase it. For example, a character could draw blatantly consume Coke or Pepsi, stop at a specific franchise restaurant to eat, or drive a particular car. Sometimes the product placement was less conspicuous, with products appearing in the background of scenes or on billboards. However, the issue with incorporating products into films like this is that the products themselves are static and unchanging. The new technology proposes to integrate variable advertisements into movies and television shows, which would be able to display whatever the streaming service company desired. For example, one might be watching a movie and the billboard that a character passes might display an ad for a soft drink. The next time one watches that scene, the billboard might display an ad for a car company. And this theory could even be applied to classic movies.

Video games already possess the technology to do this, and many sports games already incorporate these types of advertisements into them. Even certain shooter series, such as Battlefield, have integrated real-world advertisements into in-game billboards on maps.

Of course, there are hurdles to this potential future for advertising. One is that this concept is unpopular amongst old school Hollywood directors who dislike the concept of films being modified in this way. Another issue is that the technology is far more expensive that simply playing an advertisement as a separate video. Regardless, I do see increased advertising arriving in streaming media, whether of this updated version or a standardized form.

Crossovers

A corporation looks at the franchises under its control and discovers that there is a correlation between the demographics that like them. Artistically speaking, this is probably because they share themes or archetypes, portraying them in different worlds. However, from a business perspective the idea is that one need not spend money on two products to appeal to different consumer bases, one can instead spend money on a single product and attempt to gain both audiences. And so the crossover is born.

Crossovers don’t have to be bad, but the vast majority of them are artistically vapid cash grabs. Two recent examples demonstrate this. The first is the Ready Player book series/movie, which presents a world in which people escape from the dystopia around them in a virtual world known as the Oasis. Here they can choose any avatar they desire, most frequently pop culture icons (this is an example of a metaverse, as will be discussed later). At first this idea sounds like a pop culture fan’s dream come true. Everyone can pretend to be their favorite character, everyone is rewarded for all that pop culture trivia they memorized, and all the franchises of all time interact together. However, the truth is that a character means something in the context of the work they are from, because they are an exploration of an idea. Outside of that work and that idea, they are rendered as meaingless shells, skinsuits. For example, in the movie one can see groups of Spartan supersoldiers from the Halo franchise, which become just cool armor sets when removed from the Halo world. A similar fate occurs with the numerous other references in Ready Player. All are left as empty self-references, things which have the appearance of characters, but none of the true meaning. (Incidentally, if you want to listen to an amusing takedown of Ready Player One and Ready Player Two, I would recommend listening to the series that 372 Pages We’ll Never Get Back did on them.)

A second example can be cited in the recent reboot of the Space Jam movie. The original Space Jam movie was about Loony Tunes characters abducting the basketball star Michael Jordan to help them win an intergalactic tournament. This had a similar sort of blur between live action and cartoon drawings that were popularized in the earlier film Who Shot Roger Rabbit. The reboot follows the same general premise, but notably had the design decision to make the tournament a multiversal affair. This meant that characters from virtually every Warner Bros franchise were added to the movie for no reason. Thus one can see characters from Harry Potter, Game of Thrones, DC, Clockwork Orange (yes, seriously), Mortal Kombat, etc., all of which appear just for the sake of self-reference.

This attempt to find meaning in self-reference is the danger of crossovers. It is entirely possible to create an actual storyline with crossover characters. One could cite the popular Kingdom Hearts crossover series as an example of this. However, most crossovers exist just so that character X and character Y from different franchises can interact for the sake of references.

Which brings us to…

Metaverses

Metaverses represent the ultimate logical conclusion of corporate art. What is a metaverse? Imagine if a corporation had access to a half dozen video game franchises, a bunch of TV shows/movies, musical acts, and communication/social networking programs. Now imagine if all of those things were combined together in a single application, which was overlayed with some sort of gamified way of accessing and experiencing them. Additional potential addons include things like virtual workspaces and meeting rooms for office collaboration. In summary, a metaverse is part virtual experience, part streaming service, part video game, and part social network.

Of course, this entire concept runs directly into several practical issues. Virtual reality headsets are rarely comfortable enough to wear for more than an hour or two, and no one would want to wear one over an entire work day. Second, the metaverse remains a yet unproven concept. Facebook will soon release their metaverse (one which they are confident enough in to rename their entire company to “Meta”), however the only true metaverse we’ve seen so far is the one employed in the video game Fortnite. Fortnite has a multiversal storyline that incorporates characters from dozens of pop culture franchises. It has hosted several real life music concerts and discussions within the game world itself. While this outside media is displayed on a screen in game, players remain in control of their avatars, essentially watching media while also interacting with the world and chatting with one another. Fortnite has most of the elements of a metaverse, though it isn’t available on Virtual Reality systems. Thirdly, and most importantly, there isn’t evidence that people will be attracted to a single centralized application. Just because one can cram a bunch of features into an application doesn’t mean that it is a good idea to do so. Aps that attempt to provide too many services often end up being clunky and cluttered, and this is using much more accessible interfaces like touch screens and keyboards. Menu systems in VR games are notoriously worse than these options. Thus, we have technology companies making gambles to the tune of tens of billions of dollars on yet unproven systems. Success may enshrine the concept of a metaverse for the future, while failure will likely bury the idea forever.

That’s what a metaverse means from a technological perspective, but what does it imply from an artistic perspective? As worlds and franchises are combined together in a single world, redefined and remade, one is left with incoherence. Something exists and is added to the world because reference, there is no more reason than that. Ideas becomes one, a single entity for which all others exist.

Next time I will put together how Anti-Art influences wider culture.